Michael Jackson died with his books out of balance. The concerts he planned in London might have generated enough cash to pay off his debts, but a rumored Demerol injection stopped his heart before he could perform there. So he leaves this earth with as much as $500 million in unpaid debts.

Before focusing on the liability side of Michael Jackson's business, let's look at the his assets, which provided the collateral for that borrowing. He sold 61 million albums in the U.S. and had a decade-long attraction open at Walt Disney (DIS) theme parks.

Before focusing on the liability side of Michael Jackson's business, let's look at the his assets, which provided the collateral for that borrowing. He sold 61 million albums in the U.S. and had a decade-long attraction open at Walt Disney (DIS) theme parks.

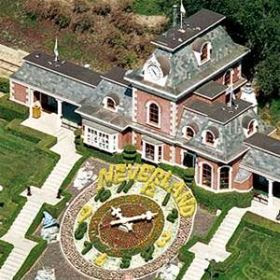

But his most valuable asset was Beatles' music -- in 1985 he paid $47.5 million for ATV Music, which owned the copyright to 259 songs written by John Lennon and Paul McCartney. A few years later, in 1988, he paid $14.6 million for Neverland, a 2,500-acre property in Santa Barbara, CA. In total, Jackson's assets may be worth $1 billion.

Jackson used some of these assets as collateral to borrow money after his album sales peaked out in the 1980s. In 1995, he merged ATV with Sony (SNE)'s library of songs and sold Sony music publishing rights for $95 million. Then in 2001, he used his half of the ATV assets as collateral to secure $200 million in loans from Bank of America (BAC). The problem was that his appetite for spending exceeded his cash inflows -- to the tune of $20 million to $30 million each year.

But the Michael Jackson magic enabled him to attract wealthy benefactors. Abdulla bin Hamad Al Khalifa, the second son of the king of Bahrain, took Jackson under his wing, giving him a palace and showering him with money in hopes that Jackson would cut an album and write an autobiography. But Al Khalifa was disappointed and sued Jackson for $7 million.

There were two more billionaires who stepped into Jackson's financial world before the end. First, Thomas Barrack, chairman and CEO of Los Angeles-based real estate investment firm Colony Capital LLC, who agreed to bail out Jackson and set up a joint venture with him to take ownership of Neverland, yielding a $23 million loan. Barrack estimated that a spruced-up Neverland could sell for as much as $80 million.

The last was conservative Philip Anschutz, who had no moral qualms about doing business with an alleged child molester. Anschutz' concert promotion company, AEG Live, planned to promote 50 shows in London's O2 arena. Tickets sold out and the first show for the ''This is It'' tour was set for July 8. AEG hoped to raise $400 million through a 3.5 year plan to work with Jackson.

But that date was delayed until July 13th as rumors of health problems surfaced. And with his sudden passing, it remains for the courts to divide up Michael Jackson's assets to satisfy his lenders.

Peter Cohan is president of Peter S. Cohan & Associates. He also teaches management at Babson College. His eighth book is You Can't Order Change: Lessons from Jim McNerney's Turnaround at Boeing. He has no financial interest in the securities mentioned.

Jackson used some of these assets as collateral to borrow money after his album sales peaked out in the 1980s. In 1995, he merged ATV with Sony (SNE)'s library of songs and sold Sony music publishing rights for $95 million. Then in 2001, he used his half of the ATV assets as collateral to secure $200 million in loans from Bank of America (BAC). The problem was that his appetite for spending exceeded his cash inflows -- to the tune of $20 million to $30 million each year.

But the Michael Jackson magic enabled him to attract wealthy benefactors. Abdulla bin Hamad Al Khalifa, the second son of the king of Bahrain, took Jackson under his wing, giving him a palace and showering him with money in hopes that Jackson would cut an album and write an autobiography. But Al Khalifa was disappointed and sued Jackson for $7 million.

There were two more billionaires who stepped into Jackson's financial world before the end. First, Thomas Barrack, chairman and CEO of Los Angeles-based real estate investment firm Colony Capital LLC, who agreed to bail out Jackson and set up a joint venture with him to take ownership of Neverland, yielding a $23 million loan. Barrack estimated that a spruced-up Neverland could sell for as much as $80 million.

The last was conservative Philip Anschutz, who had no moral qualms about doing business with an alleged child molester. Anschutz' concert promotion company, AEG Live, planned to promote 50 shows in London's O2 arena. Tickets sold out and the first show for the ''This is It'' tour was set for July 8. AEG hoped to raise $400 million through a 3.5 year plan to work with Jackson.

But that date was delayed until July 13th as rumors of health problems surfaced. And with his sudden passing, it remains for the courts to divide up Michael Jackson's assets to satisfy his lenders.

Peter Cohan is president of Peter S. Cohan & Associates. He also teaches management at Babson College. His eighth book is You Can't Order Change: Lessons from Jim McNerney's Turnaround at Boeing. He has no financial interest in the securities mentioned.

No comments:

Post a Comment